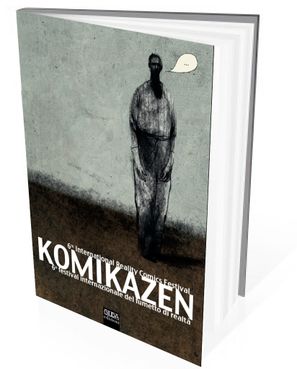

Komikazen 6° Festival internazionale del fumetto di realtà, Ravenna 2010

Since the inception 6 years ago of Komikazen and of Mirada’s first exhibitions on Sacco and Satrapi, many things have changed in the multi-faceted and structurally “impoverished” world of the comic.

The term “reality comic”, coined by us to define an object that we saw to be new and open to a different world of readers and authors, has become a subject capable of attracting the attention of publishers who are increasingly on the lookout for new forms of narrative, of magazines that are seeking presentation methods that differ from the real, of an all-consuming art market destined to become a global market, of NGOs and humanitarian organisations that are looking for new ways to recount the themes that form the heart of their work or for instruments for activities in the field.

If on the one hand this undoubtedly constitutes something highly positive and a new frontier, at the same time the ability to read the medium at its highest levels is not always there: this poverty of the reading of the medium can be summarised thus. The comic is not approached like a language in its own right, what predominates being the “importance of the medium”, the evaluation of the seriousness of the theme, whereas the result does not always match the subject. Discussing poverty is not sufficient to make a good comic. Addressing an important matter is not sufficient to make the story work. Although on the one hand authors who have undoubtedly contributed to the creation of this scenario, like Joe Sacco, state that the comic’s scope for investigation is still an unexplored continent, on the other the results produced even by major publishing projects often fall down on a didactic banality that is hard to deny.

Nevertheless, the aspects certainly of most significance and quality that have emerged are not lacking. The “dialectic realism” approach capable of producing a critical process in the reader emerges in some productions, such as for example the collective book Gaza. A representation that distances itself, denouncing its own incapability to be a direct and significant witness, that does not however waver from a determination to establish a process of dismantling of a propagandistic realism, made up of simplifications and slogans.

In a relationship of encounters and abandonments, the comic returns to the Narrative Depiction, the artistic current of the end of the 1960s that also began from an exhibition of ‘bande dessinée’ and that has plundered much from the comic. In coming out of the world of comic strip, we see the new potential of this new way of narrating coming together in the visual limitation of a style such as that of Auladell, that seriously tests traditional sequentiality in order to remain stationary in a narrative that is centred on just a single image. Instead authors who in their own bibliography have stories that were conceived from the transfigurations of reality, such as Igort, have moved on to a work of painstaking purification of fiction in order to find a true voice in the transcription of the witnesses encountered on the journey. Whereas an author like Zograf, a forerunner of the genre and now a fully fledged member of the Balkan nouvelle vague of the ninth art, has perfected a narrative technique that visually blends tried and tested reality with dreams and imagination. Publishing phenomena such as Logicomix indicate, on the other hand, that there are no longer any subject matters that are beyond the reach of the comic. And the small window opened onto the world of NGOs that use the comic as a working tool in order to achieve ethical results, the changing of the reality in which they operate and not just its representation, is just a small foretaste of a world that is coming to be inhabited by a significant number of residents…