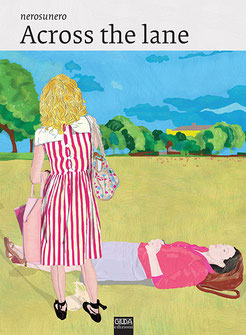

Catalog "Across the line", artist Nerosunero (Mario Sughi)

Published by GIUDA edizioni, 2014

“I think human consciousness, is a tragic misstep in evolution. We became too self-aware, nature

created an aspect of nature separate from itself, we are creatures that should not exist by natural law.”

Rustin Cohle in True Detective, The Long Bright Dark,

Season 1, Episode 1

Crossing the line between what appears and what is – this is one of the most burning narrative nubs of the multi-award-winning True Detective, the most highly acclaimed TV series of recent years. It elicits a curious reaction from a public that appears to cultivate self-referential certainties and that is accustomed to prejudice, never having been taught to experiment or to seek out sources. And yet a public that has been powerfully attracted to this blend of artistic photography, Nietzschean dialogues and sequence shots as long as those of Soviet times. Here too, in this contradictory cycle, we find the burden of our inability to accept the contemporary. We live in the information age, stunned and misinformed. Sweetened and spiked by a facebook scroll page. Pizzolatto, the writer who created the HBO series, looked out over the landscape of Louisiana, the frontier land which is also his own and where time really does appear in different dimensions, and decided to turn it into a narrative metaphor.

It is not so much a background, where complex events are played

7

out in different times, as a real space that inspires the story. It is its constant allusion, its misshapen mirror. A place that contradicts the obviousness of the reality portrayed by background chatter. It is “the truth is out there” of X Files, but without the aliens.

Nerosunero (aka Mario Sughi) does not live in Louisiana, but he appears to emerge from the same need to remove the veil from the Maja of the landscape and of the setting. Starting with his technique, which, without leave of appeal, banishes the material potential of the graven original. If reality is representation and a dream-world musing presence, the sacredness of the fetish has no reason to exist outside of its own intangible sense. His apparent painting plays on our perceptions, commandeering our astonishment (who’d have thought what a computer can do, as if it had a mind of its own, a disabled intelligence that we bring to life), just as it plays on hysterical disbelief (Oh my god! Really? Digital painting from portraits?). Ever since the 1960s, art brought this process into the mainstream, provoking cries from the doomsayers, and yet still today, in the universally accepted perception, it still manages to provoke the same reactions as it did in Beuys’s day.

Deforming details (a lamppost standing on a zebra crossing, shadows that defy the laws of physics, legless benches suspended in the air), these are the paradoxes of a context in which the body sees itself from outside of itself. It is just one thing among many, the only suspended object of a vague intellect, an entity made of pixels smiling at Schopenhauer, confirming his presence in a post-cybernetic world. The body, therefore, caught in a space that agitates it and makes it disconcerting.

It is the context that teaches the artist’s representation its narrative lesson, but it is only in the relationship between subject and object, and between landscapes that quote others that have learnt the lessons of colour from Puvis de Chavannes, from post-impressionism and Gauguin. We can all train our retina to recognise an apparently consolatory world of the imagination in what we contemplate. It might be in some trendy café, concealing its own uncanniness for the shrewd, pampered eye.

Morandi’s bottles may for example be concealed in some Internet

8

café, thus becoming popular rather than metaphysical. A kind of synaesthesia takes us back to the rancid smell shared in places devoid of relationships, other than with corroded objects, in an elsewhere that nobody really knows how to reach. In a choice between narrative knowledge and some improbable deductive, paradigmatic form of understanding, as Jerome Bruner would put it, Sughi chooses the former. In structuring concentrated sequences that focus on a single concentrated experience, the proto-hermetic mechanism that inevitably binds title to work (an authentic negation of the omnivorous Untitled) is undoubtedly one of these techniques, as we see, for example, in #814 Ahhhhhhhh!

It is true that narrative needs a sequence, necessarily putting things in order, even when pointing to the disorder of reality: the killing of the young Algerian in Camus’ The Stranger, clearly with no rational or logical link to what has gone before, and remaining this way until the end, is the narrative heart of the novel. The facts in this order show that there is no order and coincidence in the chaos of the world. For this is narrative. Painting does not contemplate this, and that is one thing. But the intentional numbering of the paintings gives an ordered sequence to a corpus of phenomena that acquire a narrative aspect.

The true detective can but train the retina and give paradox back its name, for it is the fastest tortoise. To each instant corresponds a precise clue.